The Greater Chennai Corporation's (GCC) mandate for licensing and microchipping cattle represents a groundbreaking initiative in India, positioning Chennai as the first city to enforce such measures for livestock to combat the pervasive stray cattle menace. Announced on January 30, 2026, this policy extends successful pet dog protocols to cattle, offering substantial promise for resolving urban stray issues in Chennai and potentially Tamil Nadu. By integrating radio-frequency identification (RFID) technology with regulatory oversight, the GCC aims to enhance traceability, reduce road hazards, and promote responsible ownership, addressing a national crisis affecting millions. This analytical article examines the policy's details, the underlying technology's evolution, recent innovations, comparative differences in microchip types, and its broader implications, supported by factual data and expert insights.

The Stray Cattle Crisis in India

India grapples with an estimated 5 million stray cattle, as per the 2019 Livestock Census released by the Union Ministry of Fisheries, Animal Husbandry, and Dairying, a figure slightly reduced from 5.29 million in 2012 but still indicative of a growing urban-rural challenge. Stray cattle, often abandoned due to slaughter bans in 28 states rooted in Hindu cultural reverence, cause extensive economic and safety disruptions. Nationally, they inflict annual losses exceeding Rs 11,607 crore through crop damage, with farmers in states like Uttar Pradesh and Haryana reporting up to 30% yield reductions from trampling and foraging.

How the Microchipping Technology Works

Microchipping in cattle, more accurately called electronic identification (EID) or RFID tagging, helps farmers track and manage individual animals easily and accurately. It's not like pet microchips (small implants under the skin). For cattle, the most common method uses RFID ear tags. An RFID ear tag is a small, durable plastic button or flag attached to the cow's ear. Inside, it has a tiny microchip and a thin antenna. Each tag holds a unique 15-digit number (often starting with 840 for U.S. cattle), like an ID card for the animal. This number links to a database with details like birth date, health records, vaccinations, breeding info, and movements. How it works — The tag is passive (no battery needed). A handheld or fixed RFID reader (scanner) sends out a low-frequency radio signal (usually 134.2 kHz). When close (a few inches to a few feet), the signal powers the tag's microchip. The chip then sends its unique number back as radio waves. The reader captures this instantly and shows or records the data — no line-of-sight needed, and it works even if the animal moves.

Road Accidents in Rampant

Road accidents are rampant is increasing and as per sources, between 2018 and 2022, over 900 fatalities occurred in Haryana alone due to collisions with strays. In urban settings, cattle congregate at garbage dumps, exacerbating sanitation issues and disease transmission, including zoonotic risks like bovine tuberculosis. Chennai mirrors this: official data reveal 22,875 cattle within corporation limits, with 4,237 impounded in 2024-2025, yielding Rs 2.22 crore in fines. Broader enforcement from 2021-2025 impounded 16,692 animals, recovering Rs 4.43 crore, highlighting chronic violations. These figures underscore the urgency for innovative interventions, as traditional impoundment proves reactive and insufficient.

GCC's Policy Framework and Implementation

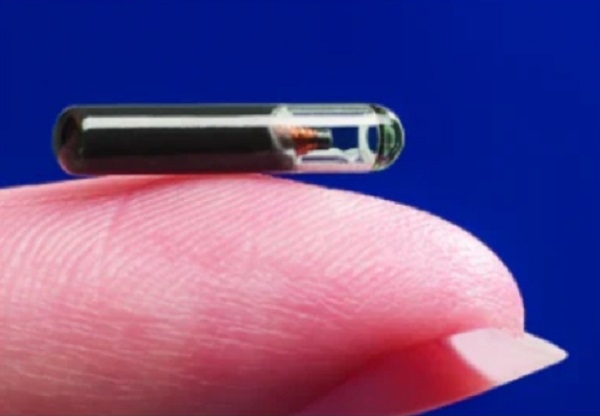

The GCC's policy, effective immediately with a compliance deadline of March 18, 2026, mandates owners to license cattle at zonal veterinary offices for Rs 100, following verification by inspectors. Each animal receives an implantable RFID microchip encoding owner details and unique identifiers, with the corporation procuring 25,000 chips and 25 readers. Non-compliance incurs Rs 10,000 fines per animal, aligning with laws like the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act, 1960, and Tamil Nadu's urban animal regulations. This builds on GCC's pet microchipping success: since 2025, over 60,000 dogs were chipped, aiding reunions and rabies control, with a 2024 census noting 180,157 strays managed via integrated QR collars and chips. For cattle, the initiative promises deterrence against abandonment, rapid offender identification, and data-driven urban planning, potentially reducing stray populations by 20-30% based on analogous global models.

Historical Evolution of RFID Microchipping

RFID microchipping for livestock traces to the 1970s, originating from U.S. military radar adaptations at Los Alamos National Laboratory for cow tracking. Early passive tags used ultra-high frequency (UHF) backscatter, evolving to low-frequency (125 kHz) glass-encapsulated implants by the 1980s for subcutaneous use. Research, including the EU's IDEA Project (1999-2001), validated RFID for disease traceability, with standards like ISO 11784/11785 establishing 134.2 kHz as the global norm. In India, while pet applications preceded, Chennai's cattle mandate is pioneering, as no prior national or state-level compulsion exists for bovines, per available records. The technology involves a biocompatible microchip (12-15 mm) storing a 15-digit code, activated by scanners emitting radio waves, enabling non-invasive reads up to 20 cm.

Recent Technological Advances

Recent advances elevate RFID beyond identification. Integration with Internet of Things (IoT) and blockchain enables real-time health monitoring: Brazilian ranches track over 500 data points per cow, from milk yield to location, reducing disease outbreaks by 25%. AI-enhanced algorithms adapt to animal physiology, improving accuracy in dense herds. Passive energy-harvesting tags, converting motion to power, extend lifespans beyond 10 years, while injectable multimodal sensors (e.g., North Carolina State's 2024 prototype) monitor vitals like heart rate and temperature wirelessly. Blockchain pairings ensure tamper-proof traceability, as in Australia's NLIS system, mandatory since 2005, slashing export rejections by 40%. In India, potential geo-fencing pilots could alert owners if cattle stray, mirroring Karnataka's 56 lakh chipped cows. These innovations address welfare concerns, with studies showing no adverse health impacts when implanted by veterinarians.

Comparative Differences in Microchip Types

Microchip types differ by form, frequency, and function. Ear tags, common for cattle, embed RFID in plastic for easy scanning but risk loss (retention rates ~95%). Ruminal boluses, ingested into the stomach, offer permanence (99% retention) but suit ruminants only. Injectable implants, as in Chennai's plan, provide discretion but require surgical precision. Frequencies vary: 125 kHz (older, U.S.-centric, shorter range) versus 134.2 kHz (ISO-standard, universal compatibility). Passive chips dominate for cost (Rs 100-1000) and longevity, unlike active ones needing batteries for extended range but impractical for mass use. Differences impact adoption: ear tags suit large-scale farming, implants urban traceability.

Analytical Implications and Challenges

Analytically, Chennai's policy could transform urban livestock management, fostering accountability and reducing incidents by enabling swift impounds. Experts like those from the International Committee for Animal Recording praise RFID for breed improvement and economic gains, potentially boosting Tamil Nadu's dairy sector (valued at Rs 50,000 crore annually). Challenges persist: high initial costs (Rs 25 crore for GCC's procurement), compliance resistance (as seen in pet drives with extensions), and privacy concerns over data misuse. Veterinary training is crucial to avoid migration or rejection (rates <1%). Broader rollout demands stakeholder buy-in, with pilots in other cities like Delhi or Mumbai to assess scalability.

Conclusion

In conclusion, GCC's mandate heralds a tech-driven era for India's stray cattle crisis, blending innovation with policy for sustainable urban harmony. As a first-of-its-kind effort, it sets a replicable model, provided implementation addresses gaps. (Author is Associated with Hindusthan Samachar as Representative of Tamilnadu State)

References/Sources/Further Reading :

1. Government of India. (2019). 20th Livestock Census. Ministry of Fisheries, Animal Husbandry and Dairying.

2. Pathak, S. (2023). India's 5 Million Stray Cows. National Geographic.

3. Caja, G., et al. (1999). Electronic Identification of Livestock. EU IDEA Project Report.

4. Zimmerman, P. (2025). RFID in Livestock Management. C-Lock Inc. Publications.

5. IEEE Sensors Journal. (2024). Injectable Multimodal Sensors for Animals.

---------------

Hindusthan Samachar / Dr. R. B. Chaudhary